|

OVERVIEW

It is impossible that William Webb Ellis invented Rugby

Union. The theory that he did is contained in a publication dated 1897,

called ‘The Origin of Rugby Football’. At the time the William Webb

Ellis Event was accepted as the origin, however it is now generally

accepted by historians that this event is not the origin of the sport of

Rugby Union. The author of the publication ‘The Origin of Rugby Football’

states that Matthew Bloxam, who was dead and unable to challenge the

findings wrote that Webb Ellis invented Rugby Football. However, in the

writings of Bloxam, he only stated that Webb Ellis started the change in

one of the rules, he was unsure in which year Ellis did this (1823, 1824

or 1825) and this he learned from a unnamed third party between February

and October of 1876. Bloxam was told about the William Webb Ellis event 53

years after it is supposed to have happened and 4 years after William Webb

Ellis died. Bloxam's view was that Webb Ellis was playing the same game

that he was playing while he was a pupil at the school 1813-1920. This

being the case in 1823 Webb Ellis was already playing Rugby Football, a

game where you could only win a match by kicking the ball between the

posts and over the crossbar, Bloxam was not of the opinion that Webb Ellis

invented a game, his opinion was that Webb Ellis only started a change in

one of the rules of Rugby Football, the same game he played in 1813.

The common modern misconception is that Webb Ellis was

playing Association Football. This is impossible because the game of

Association Football was not invented until 1863.

The report ‘The Origin of Rugby Football’ is written

by a group of Old Rugbeians (former Rugby School pupils) whose sole

intention is to place the 'origin' of Rugby Football at Rugby School, they

didn't care how they did it and they used methods of deception to credit

Webb Ellis with the invention of Rugby Football.

Please see our detailed analysis for confirmation of this:

AN ANALYSIS OF THE

WILLIAM WEBB ELLIS EVENT

BACKGROUND

The theory that the William Webb Ellis event was the origin of Rugby Union didn’t begin in 1823, but instead began 74 years later in 1897 with the publication of a report by a sub-committee of the Old Rugbeian Society called ‘The Origin of Rugby Football’. The conclusion of that report is that the origin of Rugby

Football began with William Webb Ellis in 1823.

“…..that this was in all probability done in the latter half of 1823 by Mr. W Webb Ellis, who is credited by Mr. Bloxam with the invention and whose ‘unfair practices’ were (according to Mr. Harris) the subject of general remark at the time.” –

ORSR022

(links in blue are to the original page on which each quote is taken)

|

|

|

The only known portrait of William Webb Ellis, 1857 |

THE 1897 REPORT ON THE ORIGIN OF RUGBY

More of Webb Ellis later, but firstly, because the report is so important in pinpointing the Webb Ellis event as the origin of Rugby

Football, let’s look at the report in its entirety. Why was it commissioned? Who wrote the report? What are its conclusions? Are these conclusions correct? Did it take into account all of the available information? There are so many questions to be asked that we’d better make a start on it pronto, and where better to start than at its beginning:

“In the “Athletics and Football” volume of the Badminton Library – in almost every respect a most painstaking and praiseworthy book – the author, Mr. Montague Shearman commits himself to certain statements about the Rugby game which we venture to consider misleading, if not altogether erroneous.” –

ORSR003

WHY WAS THE REPORT COMMISSIONED?

Montague Shearman knew how to kick up a storm. The below paragraph in the Football section of his book in the chapter ‘History’ upset the Old Rugbeians, who had studied and played the game at the school that had given its name to the sport now called Rugby Union. Rugbeians had always believed that this was their game, a game they had invented and showed the world how to play. This was their sport, but this was Shearman’s conclusion:

“Now at the present day every large school has a good large grass playground either in the grounds of the school itself or within convenient reach; but in the olden times little or no provision for ‘playing fields’ appears to have been made by pious or other founders. One school alone seems to have owned almost from its foundation a wide open grass playground of ample dimensions, and that school was Rugby; hence it happens as we should have expected, that at Rugby School alone do we find that the original game survived almost in it’s primitive shape.” –

MSAF271 & MSAF272

From the opening paragraph we can surmise that the reason that the report was commissioned was to dispute Montague Shearman’s claim that the ‘original’ version of folk football survived at Rugby School because it had a large playground (wide open spaces) and because Rugby Union at the time of his book had similarities with folk football, in that you were allowed to carry the ball. The Old Rugbeian Society found Montague Shearman’s conclusions to be

“misleading, if not altogether erroneous”.

WHAT WAS THE PURPOSE OF THE REPORT?

The purpose of the report was to place the ‘Origin of Rugby Football’ at Rugby School. Its aim according to the opening paragraph was:

“… to investigate these statements, and also to enquire into the account of the origin of our game put forward on more than one occasion by the late Mr. Matthew Holbeche Bloxam…” –

ORSR003

The report needed to discredit Shearman so that the origin of Rugby Union could be placed at Rugby School. To do this the sub-committee needed to prove two things:

1 – That Rugby School did not originally have wide open spaces where a game of folk football could have survived.

2 – That Football at Rugby School was mainly a kicking game, which then developed into a handling game.

DID THE REPORT PROVE THAT THERE WERE NO OPEN SPACES FOR FOLK FOOTBALL TO SURVIVE?

Yes it did. On the subject of the open spaces, the committee suggested that Shearman should have consulted an Old Rugbeian on this matter. They name the three authors of the Winchester, Eton & Harrow chapters from Shearman’s book and state:

“He does not, however, appear to have consulted any Old Rugbeian to the same extent with reference to the Rugby game, and it is probably due to this fact that, as we hold, he has fallen into error. In his other book on the same subject, ‘Football : Its History for Five Centuries’, (Field & Tuer 1885), written, as he informs us, in conjunction with Mr. Vincent, he discussed the origin of the various forms of School football: and the conclusion arrived at in that work was that ‘in each particular school the rules of the game were settled by the capacity of the play-ground; and that as these were infinitely various in character, so were the games various.’ ” –

ORSR003

The report is selectively quoting Shearman here, although at least getting the title of his 1885 work correct. In ‘Foot-ball – Its History for Five Centuries’, Shearman did state that Rugby School was the exception to this rule, and in 1887 he is just confirming his earlier diagnosis. The big picture, however, is that in that book Shearman makes Rugby School the public scapegoat, so that his folk football origin theory can be traced back to ancient times and the ‘original game’, because as

we will show in a future article, it’s almost impossible to link folk football to being the origin of Rugby

Football.

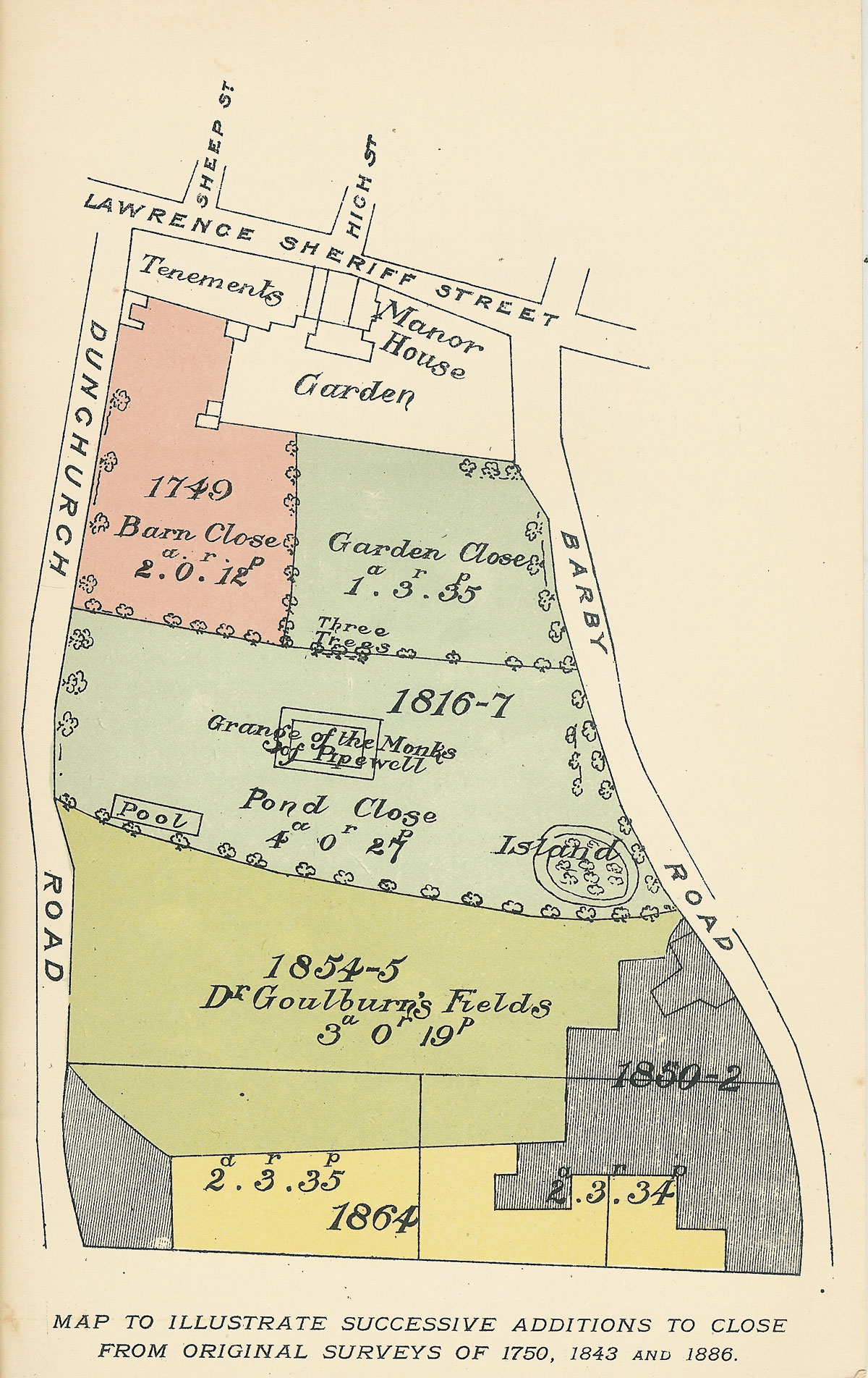

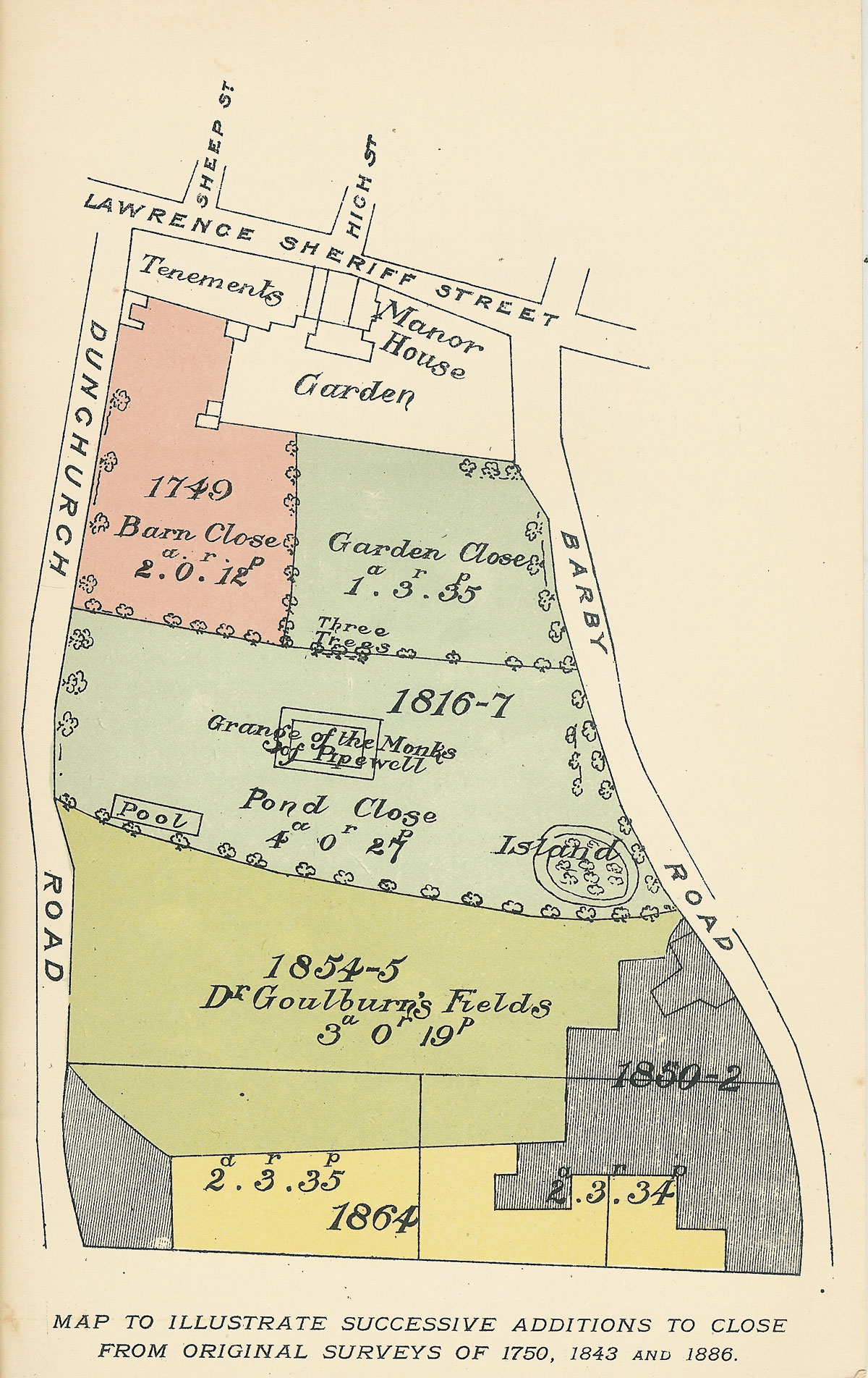

The report argues its case about the school having “from its foundation a wide open grass playground of ample dimensions”

(MSAF271 & MSAF272) by listing the various additions to Rugby Close (the area in which Football was played) and publishing maps that highlight these. The school had moved from the middle of town with no playground to a Manor House with fields on the edge of town in 1750 (MBRN003).

|

|

|

Map of Rugby School Close with additions |

The report also draws on the article written in the Meteor by the local historian Matthew Holbeche Bloxam who stated that there was a limited amount of space for play:

“An article in the Times newspaper, the leading journal of Europe, a few weeks past, on the Rugby School Football Rules and play, as contrasted with the Association Rules, has prompted me to write a few words on the game of football, as played at Rugby in my time, 1813–1820. The last time I played at Bigside in the Close was just 60 years ago, and my recollections of the game extend to 67 years… In 1813, the available space for the play-ground was not more than four acres at the most…The island was in a separate field from the Close, and the southern part of the present Close was divided into fields, and formed a small dairy farm. Cricket and Football at Bigside were played at the north-west corner of the Close, adjoining the Dunchurch Road. One of the goals was erected on the site of the Chapel, not then in existence.

When preparations for the erection of the chapel were made and the ground enclosed for that purpose, circa A.D.1817–18, Bigside both at Cricket and Football was removed to that part of the close lying immediately South of the headmaster's garden wall.” –

ORSR008

The report continues with Bloxam’s account of Football at Rugby School then breaks for its ‘open spaces’ conclusion before moving seamlessly into the Webb Ellis theory.

“In the passage just quoted another blow is given to Mr. Shearman’s cherished theory, that Rugby preserved “the primitive game”. We have already shewn that until 1749 Rugby was without any play-ground for football at all: and when the purchase of the manor-house and its enclosures supplied the deficiency, the game that was played (according to Mr. Bloxam’s testimony) was not the game that Rugby knows now, but something more resembling Association Football” –

ORSR009

There we have it, in a nutshell and in one small paragraph, until 1749 there was no playground and the game was like Association football (soccer), according to Matthew Bloxam of course. But just in case we’ve missed something let’s check out how the report proves that Football at Rugby School was a kicking game and how William Webb Ellis invented the running game.

DID THE REPORT PROVE THAT RUGBY WAS A KICKING GAME?

This account of early Football at Rugby School is what gave birth to the legend that William Webb Ellis invented rugby football. Correspondence with former pupils and extracts from the 1880 article by Matthew Bloxam, submitted to the Rugby School old boys periodical the ‘Meteor’ No 157 22 December 1880, appear in the report. The editor’s introduction to Bloxam’s account of the Webb Ellis event is of critical importance because he states that this is the “origin of the present rugby game”:

“We now come to Mr. Bloxam’s account of the origin of the present rugby game, which is of such importance that we print it in extenso.”

“In the latter half of 1823, some 57 years ago, originated, though without premeditation, that change in one of the rules which more than any other has since distinguished the Rugby school game from the Association Rules.

A boy of the name of Ellis - William Webb Ellis - a town boy and a foundationer, who at the age of nine entered the school after the midsummer holidays in 1816, who in the second half-year of 1823 was, I believe, a præposter, whilst playing Bigside at football in that half-year, caught the ball in his arms. This being so, according to the then rule, he ought to have retired back as far as he pleased, without parting with the ball, for the combatants on the opposite side could only advance to the spot where he had caught the ball, and were unable to rush forward until he had either punted it or placed it for someone else to kick, for it was by means of these placed kicks that most of the goals were in those days kicked, but the moment the ball touched the ground, the opposite side might rush on. Ellis, for the first time, disregarded this rule, and on catching the ball, instead of retiring backwards, rushed forwards with the ball in his hands towards the opposite goal, with what result as to the game I know not, neither do I know how this infringement of a well-known rule was followed up, or when it became, as it is now, the standing rule. Mr. Ellis was high up in the school, and as to scholarship of fair average abilities. He left the school in the summer of 1825, being the second Rugby Exhibitioner of that year, and was entered at Brasenose College, Oxford. He subsequently took Holy Orders, and at a later period became Incumbent of the church of St. Clement Danes, Strand. He died on the Continent some years ago. When at school, though in a high form, Mr. Ellis was not what we should call a ‘swell,’ at least none of his compeers considered him as such; he had, however, plenty of assurance, and was ambitious of being thought something of. In fact he did an act which if a fag had ventured to have done, he would probably have received more kicks than commendations. How oft it is that such small matters lead to great results!” –

ORSR009

The report continues and it’s worth quoting the text that follows for the conclusions reached by the editor:

“Mr. Bloxam’s very circumstantial account of Mr Ellis’s exploit, though not that of an eye-witness (for he had left the school some three years before) cannot be ignored, and though we have been unable to procure any first hand evidence of the occurrence, we are inclined to give it our support. Some one must have broken through the rule against running with the ball, and Mr. Bloxam (who is a fellow-townsman of Mr. Ellis and was at the time, we believe, pursuing his legal studies in Rugby) had evidently satisfied himself of the accuracy of the story. He had previously broached the subject, as he tells us in a letter headed “Football and Athletics” to the Meteor (No. 104) of October 10, 1876 by writing to the Standard (in which a discussion on the game had been taking place) to controvert the belief, expressed by one of its correspondents that the Rugby game, at present played at Rugby, was ‘of great and unknown antiquity’. He then stated, that instead of this being the case, the present game, so far as the rules authorised the ball being carried by hand, the holder running with it, was unknown during the time he was at school, viz. 1813 to 1820, and went to say that he thought it was introduced in Dr. Arnold’s time. In the letter to the Meteor, however, he says he had “since ascertained” that the change originated, in the manner already detailed above, in the second half year of 1823, that at first it did not succeed, but was soon set aside, and was not again introduced until Dr Arnold’s mastership 1828–1842.” –

ORSR010

The next section in the report is dedicated to the correspondence of former pupils and it contains most interesting information in relation to the game, how it was played and the rules. One letter is from a former pupil, Thomas Harris, who was familiar with Webb Ellis and whose time at Rugby School overlapped Ellis’. The letter was written to Henry Homer who had contacted Harris on behalf of the ORS.

“1. Picking up and running with the ball in hand was distinctly forbidden. If a player caught the ball on a rebound from the ground or from the stroke of a hand, he was allowed to take a few steps so as to give effect to a ‘Drop-kick,’ but no more: subject of course to interruption from the adverse players. I remember Mr. William Webb Ellis perfectly. He was an admirable cricketer, but was generally regarded as inclined to take unfair advantages at Football. I should not quote him in any way as an authority.

2. If the ball was caught in the hands from a kick, the catcher was entitled to ‘place try’ at goal, retiring a sufficient distance from the place where the catch was made.

3. All laying hands upon and holding a player was strictly forbidden under any circumstances.

I do not remember any other material points in connection with Football: a grand game as I used to consider it, as formerly played. I may add that my brother John Harris, who left rugby in 1832, and who was a devoted lover of the game, agrees with me in the particulars given above. He happens to be at this time staying with me.” –

ORSR020

The ORS wrote again looking for more information and the reply from Thomas Harris was as follows:

“I’m afraid that I can add but little to the recollections of Rugby Football which I gave in my letter to Homer. As to Mr. W. Webb Ellis and his practices, you must observe that I was several years his junior, and had not either reasons or opportunities for closely observing his manner of play. I am sure, however, that it was very generally regarded as unfair by the leading players of the day. It may be that his practice of running with the ball, which Mr. Matthew Bloxam speaks of as having been invented by him, was the point objected to; but of this I cannot speak from my own observation.

I may add that in the matches played by boys in the lower part of the School, while I was myself a junior, the cry of “Hack him over” was always raised against any player who was seen to be running with the ball in his hands. Our laws in those days were unwritten and traditionary, so that I can give no authority beyond custom.” –

ORSR022

Harris confirms that Webb Ellis is a cheat, which backs up Matthew Bloxam’s account of Webb Ellis running forward with the ball, and the committee consider that they have proven that Football at Rugby School was a kicking game before it became a handling game. The report’s editor then comments on the Webb Ellis event after receiving Thomas Harris’ second letter:

“It may, we think, be fairly considered to be proved from the foregoing statements, that (1) in 1820 the form of football in vogue at Rugby was something approximating more closely to Association than to what is known as Rugby football to-day, (2) that at some date between 1820 and 1830 the innovation was introduced of running with the ball, (3) that this was in all probability done in the latter half of 1823 by Mr. W. Webb Ellis, who is credited by Mr Bloxam with the invention and whose ‘unfair practices’ were (according to Mr. Harris) the subject of general remark at the time. To this we would add that the innovation was regarded as of doubtful legality for some time, and only gradually became accepted as part of the game, but obtained a customary status between 1830 and 1840, and was duly legalized first by Bigside Levee in 1841–42 (as stated by Judge Hughes) and finally by the Rules of 1846 (Appendix A).” –

ORSR022

WHO WAS BLOXAM’S SOURCE?

Matthew Bloxam’s younger brother John Rouse Bloxam was still alive in 1876 and it is generally thought that as John was a contemporary of Webb Ellis, leaving Rugby School at around 1826 (to be confirmed), it is probable that Bloxam senior obtained the Webb Ellis information from him.

WHAT WERE THE CONSEQUENCES OF THE REPORT?

Firstly, Montague Shearman puts his hands up and says he was wrong. In the first edition of his book titled ‘Football’, published in 1899, he states in his chapter on the history of the game, a previous version of which appeared in ‘Athletics and Football’:

“Since this chapter was written, in 1887, a sub-committee of the Old Rugbeian Society (consisting of Messrs. H. F. Wilson, H.H. Child, A.G. Guillemard, and H.L. Stephen) has paid me the compliment of making a searching investigation, both from historical documents and from inquiry from living Old Rugbeians, with the view to testing my theory that ‘at Rugby alone was the old running and collaring game kept up.’ The result of their inquiries has been embodied in a pamphlet entitled ‘The Origin of Rugby Football,’ and published by Mr. Laurence, of Rugby. The writers point out that I was incorrect in my statement that ‘Rugby seems to have owned almost from its foundation a wide open grass playground of ample dimensions,’ and show that the school had no regular playground until 1749, when it obtained one of 2 a o r. 12 p., and no really ‘ample playground’ until 1816–17; and the net result of their researches is summed up as follows…” –

MSFT034

Then he quotes directly from the Old Rugbeian Society report:

“It may, we think, be fairly considered to be proved from the foregoing statements that (1) in 1820 the form of football in vogue at Rugby was something approximating more closely to Association than what is known as Rugby football to-day; (2) that at some date between 1820 and 1830 the innovation was introduced of running with the ball; (3) that this was in all probability done in the latter half of 1823 by Mr. Webb Ellis…To this we would add that the innovation was regarded as of doubtful legality for some time, and only gradually became accepted as part of the game, but obtained a customary status between 1830 and 1840, and was duly legalised first by Bigside Levee in 1841–42 (as stated by Judge Hughes), and finally by the rules of 1846.” –

MSFT035

A year later, the Old Rugbeian Society, confident of no opposition, lay the plaque in the wall of the Headmaster’s Garden at Rugby School.

It is this plaque more than anything that has perpetuated the William Webb Ellis event as being the origin of Rugby Union. So where do we go from here? Do we accept the report as having proven the origin of Rugby Union? Or shall we check out its conclusions to see if they are correct? I find that the best way to analyse something is to ask questions, so let’s start asking questions relating to this report to see if we can find the answers, and let’s keep asking questions until we are happy that we’ve found them.

Let’s start at the beginning and look at Shearman’s claims. If Shearman’s first edition of Athletics & Football was published in 1887 and his chapter on the history of Rugby Union remained the same, then we should be asking this question:

WHY DID IT TAKE EIGHT YEARS (UNTIL 1895) FOR THE REPORT TO BE COMMISSIONED?

I believe that the reason for this is that the report was actually commissioned to discredit the chapter ‘Origin of the Game’ in the first ‘complete’ rugby history by the Reverend Frank Marshall, ‘Football – The Rugby Union game’, first published in 1892. In that book Marshall had leaned heavily on Shearman’s work for his references to the origin, but had come up with the conclusion that Rugby had evolved from the game the Romans had called harpastum.

“That the Romans, who occupied this island during the first four centuries of the Christian era, played at a game of ball called harpastum, which game presented the special features of carrying the ball and the scrummage, found in no other modern game of football save in the Rugby

game…” – FMRU012

Whilst Shearman was non-committal in pointing the finger at what the ‘original game’ was, Marshall had pointed the finger at harpastum and moved the evolution goalposts firmly to the Italian invaders. To understand why the report targets Shearman instead of Marshall, we need to ask another question:

WHO COMPILED THE REPORT?

According to the front cover, it was a sub-committee of the Old Rugbeian Society. We have to turn to page 27 of the report to see who the members of this sub committee were. They were a group of four and before I tell you who they were, I’m going to give them a collective name. From now on, I’m going to call them ‘the plaque in the wall gang’.

Henry Francis Wilson, son of the Rev. William Greive Wilson, Rugby, attended Rugby School 1873–1878. He was a barrister by profession and was called to the bar in 1888 before embarking on a career in the civil service, chiefly as a legal advisor in the Colonial Office. He was appointed Secretary of the Trinidad Judicial Enquiry Commission in 1892 and was Secretary of the Orange River Colony in South Africa from 1902 to 1907. Other posts included that of Secretary of the Royal Colonial Institute (1915–21). He was knighted in 1908.

Herbert Henry Child was the second son of William Henry Child, Esq of Rugby. He attended Rugby School in 1870–1875 before moving on to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he obtained his B.A. in 1878. His profession was Barrister-at-Law, practising in Lincoln's Inn from 1882.

Arthur George Guillemard was a former pupil of Rugby School, 1859–1864. Guillemard had played for England in the first international in 1871, was a founder member of the RFU and had served on its committee as a Senior and Junior Vice-President, as Hon Treasurer, Hon Secretary and President. He was the fifth President of the Rugby Football Union (the previous four presidents had all been schooled at Rugby). At the inaugural meeting, it was his proposal to name the newly formed society the ‘Rugby Football Union’. He refereed six internationals between 1877 and 1881

(JGPR103) and had acted as an umpire on the sidelines before referees were first appointed for matches in 1876. He was a solicitor.

Harry Lushington Stephen was the third son of Mr. Justice James Fitzjames Stephen. He attended Rugby School from 1874 to 1877 and studied at Trinity College, Cambridge. He was knighted in 1908 and his profession was barrister-at-law (Inner Temple 1885).

The plaque in the wall gang had of course all studied at Rugby School. Guillemard knew the game inside out, but more importantly, the Old Rugbeian had put pen to paper in Marshall’s 1892 work in the second chapter ‘A Bigside at Rugby’, which included a large extract from Tom Brown’s Schooldays. He also wrote Chapter VII ‘The Foundation and Progress of the Rugby Football Union’. I believe that because the Rugby man was a contributing writer in that book, the sub committee of which he was a member couldn’t be seen to be attacking Marshall’s work. To have disputed Marshall’s origin theories in the report would have discredited the whole of the book, including Guillemard’s own chapters in which he sang the praises of Rugby School and the Rugby Football Union. So the Old Rugbeian Society had no other option but to contest the origin theories in Shearman’s book instead, which is quoted as the main source of reference for Marshall’s initial chapter on the origin of rugby.

Frank Marshall’s first edition was published in 1892. It’s possible that Arthur G Guillemard had a chat with Marshall and asked him to review his chapter on the origin. If he did, Marshall clearly didn’t listen because two years later, just a year before the report was commissioned, the revised and enlarged edition of Marshall’s book was published, with Chapter 1 remaining the same, errors included. Also rubbing salt into the Rugby School wounds in 1894 was Montague Shearman, publishing the fourth edition of ‘Athletics and Football’.

To me it makes more sense that this is the reason why the Old Rugbeian Society commissioned the report, to halt the ever increasing momentum of the folk football origin theory, and in particular Marshall’s theory that the game the Romans called harpastum was the origin of Rugby Football. We should now ask questions to see whether the information contained in the report is correct.

DID THE REPORT PROVE THAT THERE WERE NO OPEN SPACES FOR FOLK FOOTBALL TO SURVIVE?

Yes – the evidence is pretty conclusive. Until 1749 Rugby School was in the middle of the town and there was no dedicated playground for the boys. This information is readily available in sources relating to the history of Rugby School.

DID THE REPORT PROVE THAT RUGBY WAS A KICKING GAME?

Yes it did. Matthew Bloxam’s 1880 article in the Meteor gives a good description of the nature of the game as played in his time at the school, 1813–1820. He states that those keeping goal were

“watching their opportunity for a casual kick”

(ORSR009),

“It was Football, and not Handball, plenty of

hacking” (ORSR009) and

“until he had either punted it or placed it for some one else to kick, for it was by means of these placed kicks that most of the goals were in those days

kicked” (ORSR010). Football at Rugby School was a kicking game, because it was illegal to pick a ball up off the floor, passing the ball was not allowed and running forward with the ball was taboo, so when the ball was on the floor there was no other choice than to kick it. If it was rolling forward towards you, maybe you could have stopped it with your hands then kicked or knocked it forward with your hands. But a kick would help the ball travel further and it was also a lot easier to do. Of course the most important factor – the objective of the game in Football at Rugby in 1813 was to score a goal by kicking the ball over the crossbar and between the posts. Football at Rugby School was a kicking game.

DID WEBB ELLIS REALLY RUN WITH THE BALL?

If what Webb Ellis did was so momentous, then it would have passed into Rugby School folklore and remained so. Yet, according to the report, pupils entering Rugby School less than five years after Ellis had left had never heard of him.

In writing in the Meteor in 1879, Matthew Bloxam says of the pupils around that time (1809):

“At this time boys not unfrequently continued at School ten or even twelve years, and traditions of a longer date were handed down than at the present time, keeping remembrance of any stirring event alive.” –

MBRN087

If what Webb Ellis did was notable, a stirring event, either as a good or a bad thing, it would surely have been recorded in Rugby School folklore as the ‘Webb Ellis rule’, or something similar. The fact that it was not throws doubt onto the authenticity of the Webb Ellis event.

IS THE WILLIAM WEBB ELLIS EVENT THE ORIGIN OF RUGBY UNION?

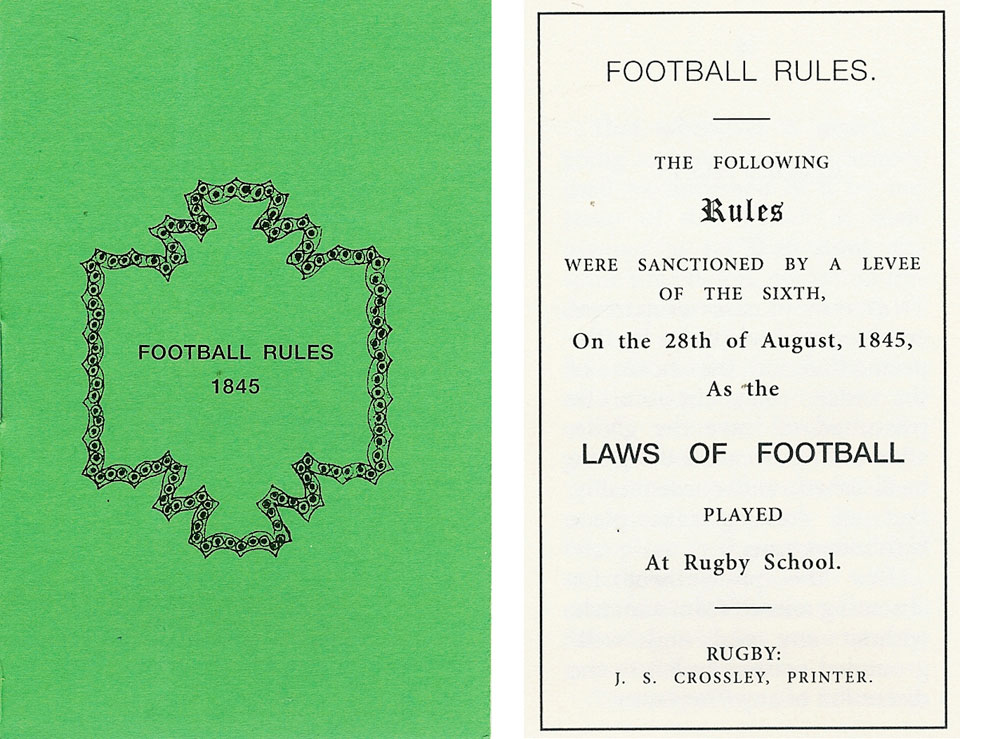

No it isn’t. You don’t need to be a rocket scientist to figure out that if Webb Ellis broke a rule then he must have been playing a game. What game was he playing? According to Matthew Bloxam, between 1813 and 1820 he was playing Football. So what game were they playing in 1845 when they wrote the first ‘Football Rules’? The clue is in the name, they were playing Football. It’s the game I’ve termed

‘Rugby Football’ to set it aside from other forms of football because

it was Football played at Rugby School. It’s the same game that the Old

Rugbeians were playing when they formed the Rugby Football Union to create

the new sport of Rugby Union. Let’s return to the consequences of the report and remind ourselves of the wording on the plaque:

|

THIS STONE

COMMEMORATES THE EXPLOIT OF

WILLIAM WEBB ELLIS

WHO WITH A FINE DISREGARD FOR THE RULES OF FOOTBALL

AS PLAYED IN HIS TIME

FIRST TOOK THE BALL IN HIS ARMS AND RAN WITH IT

THUS ORIGINATING THE DISTINCTIVE FEATURE OF

THE RUGBY GAME

A.D. 1823 |

Looking at what Wallace Reyburn says in his 1971 ‘A history of Rugby’, he opens the book with:

“It is a popular misconception that during the course of a soccer match in 1823 a young fellow ran with the ball thus sowing the seed for a handling game which made a radical breakaway from the sport which was literally football. But in fact it was not as clear cut as that. What the Ellis boy did in 1823 at Rugby School was merely to add a new dimension to a handling game already in existence. The match in which the incident took place was certainly not soccer, since catching was allowed to any member of the team. There was, however, a restriction on running with the ball. This could only be done back from the mark at which the catch was taken; if the catcher wanted to go forward he could do so only as a follow-up to his kick ahead. The revolutionary thing that young Ellis did was to run forward with the ball in his hands.” –

WRHR001

Reyburn had the gist of it but then forgot about the origin and went on to write the rest of rugby history. Let’s look closely at two sets of words on the plaque. To the layman it would seem that as Reyburn suggests above, a game of soccer was interrupted and spoiled by the upstart Ellis.

“… the rules of football as played in his time…”

“… distinctive feature of the Rugby game…”

When William Webb Ellis played the game it was called football, but by the time the plaque was placed in the school

there was a new game called Rugby Union Football which was based on the

same sport that Webb Ellis played. This sport was popularly known as

'rugby' because Association Football had adopted the term 'football'. To understand this development we need to follow the path of evolution for these

sports; this is well documented in history so all that’s required here is a simple outline of the major landmarks in the sport’s history:

1805 – Earliest accepted mention of Rugby Football (Macready’s Reminiscences & Diaries)

1813 – Bloxam enters Rugby School and plays well organised football that has a set of verbally agreed rules

(Rugby Football)

1823 – Ellis allegedly runs forward with the ball in a game that has a set of verbally agreed rules

(Rugby Football)

1830–40 – Running forward with the ball is allowed (Rugby Football)

1841 – “Running in” (scoring a touch down, a predecessor to the try) is allowed

(Rugby Football)

1845 – The first set of Football Rules are drawn up for 'Football' at

Rugby School. (Rugby Football)

1845–1862 – Old Rugbeians start to take the Rugby Football rule book to universities, other schools and into towns and cities where they form football clubs that play under the

Rugby School Rules. When the game was then played in locations other than at Rugby School,

Rugby School became known as football as played under the Rugby School Rules, or its condensed version, Rugby School

Rules, latterly known as Rugby Football.

1862 – The Rugby Football Rule book is widely distributed to clubs, universities and schools that are playing the game.

The pitch is given dimensions so that it can be played anywhere with a

space large enough.

1871 – Teams playing Rugby School (Football) Rules form a governing body to oversee the clubs involved. The new governing body is called the Rugby Football Union and a new

and different set of rules, (based on the Rugby Football Rules), are drawn up by

a sub-committee of three Old Rugbeians (A. Rutter, E. C. Holmes and L. J. Maton).

L.J. Maton is credited with writing the laws. The sport of Rugby Union is created.

1872 - William Webb Ellis dies aged 65, he is not to be credited with

inventing the sport of Rugby Union for another 24 years.

1875 - Two different forms of rugby exist Rugby Football

played at Rugby School and administered by the boys of Rugby School and

Rugby Union administered by the Rugby Football Union. They are

administered by different organisations, they have different rules and are

played by different people therefore they must be different sports.

1876-1890 - With limited opposition to play under the

Rugby Football rules, Rugby School slowly phases out the sport of Rugby

Football and in 1890 Rugby School formerly join the Rugby Football Union.

Rugby Football. The annual School v Old Rugbeians match is still played

under Rugby Football rules until approximately 1900.

1886 – (Rugby) International Board formed

1890 – All international matches are to be played under the same laws,

those laws are to be those presently existing of the Rugby Football Union,

with minor alterations. (OLOE1955RFU338) OL Owen History of the RFU 1955

1895 – Breakaway of Northern Union clubs (creation of Rugby League)

1900 – Plaque placed in Rugby School

1930 – All teams to play under International Rugby Board rules, as opposed to under the rules of their nation’s Union

2019 – The International Rugby Board is now known as World Rugby

As mentioned previously, the evolution of the games from that played at Rugby School to that played today is well documented, and as you can see from the above timeline, the same game was played by Matthew

Bloxam in 1913, William Webb Ellis in 1823 and Arthur Guillemard in the

1860s. Guillemard and his friends created a new sport in 1871 which had a

different set of rules and was eventually played by the likes of Wavell

Wakefield, Jackie Kyle, Ian McGeechan, Willie John McBride and Richie McCaw.

What’s thrown a spanner into the working mind of the 20th & 21st century human being, that’s you and I, is that the Association football game (soccer) that started in 1863 naturally assumed the term football, because it is played with the feet, and so we’ve grown up recognising football as being the round ball game. But if we cast our minds back to the first football history, George Routledge’s ‘A handbook of

Football’ in 1867, we see that football was a very broad term, covering folk football, the school games (including Rugby School

Football Rules) and Association football.

At Rugby School, Webb Ellis was playing football because that’s what everybody called it back then. By 1900, however, the term football was generally used to refer to Association

Football only. In 1900, the Rugby Union game which was a descendant of the

same game that was known as football in 1823 was known as 'rugby'. Therefore, William Webb Ellis did not invent Rugby Union. Which leads us to ask the question “what made us believe that he did?”

WHY DO WE THINK THAT WEBB ELLIS WAS PLAYING ASSOCIATION FOOTBALL?

It’s back to the report of the Old Rugbeian Society where we find that there are three passages that mention Association football. The first mention is by the editor as he comments on Bloxam’s information:

“In the passage just quoted another blow is given to Mr. Shearman’s cherished theory, that Rugby preserved “the primitive game.” We have already shewn that until 1749 Rugby was without any play-ground for football at all: and when the purchase of the manor-house and its enclosures supplied the deficiency, the game that was played (according to Mr. Bloxam’s testimony) was not the game that Rugby knows now, but something more resembling Association Football.” –

ORSR009

The second is by Bloxam and it appears early in his 1880 article in the lead up to his description of the Webb Ellis event:

“In the latter half of 1823, some 57 years ago, originated, though without premeditation, that change in one of the rules which more than any other has since distinguished the Rugby school game from the Association Rules.” –

ORSR009

The third is again by the editor, commenting on the Webb Ellis story after receiving Thomas Harris’ second letter:

“It may, we think, be fairly considered to be proved from the foregoing statements, that (1) in 1820 the form of football in vogue at Rugby was something approximating more closely to Association than to what is known as Rugby football to-day, (2) that at some date between 1820 and 1830 the innovation was introduced of running with the ball, (3) that this was in all probability done in the latter half of 1823 by Mr. W. Webb Ellis, who is credited by Mr Bloxam with the invention and whose ‘unfair practices’ were (according to Mr. Harris) the subject of general remark at the time.” –

ORSR022

So there are the three mentions of Association football and it must be noted that numbers 1 and 3 are meant to reflect what is said in number 2.

1 – “…but something more resembling Association Football.”

2 – “…which more than any other has since distinguished the Rugby school game from the Association Rules.”

3 – “… approximating more closely to Association than to what is known as Rugby football to-day…”

I may be being picky here, but to me number two (Bloxam) says that the sports are different and that handling is the biggest difference between the two, whereas numbers 1 and 3 (report editor) say that the games of Association football and Football at Rugby School were similar. It’s an extremely clever and sophisticated ruse if number one was placed in front of number two to pre-suggest this and then number three was placed later on in the report to confirm what number one suggested. It certainly has the effect of making the reader believe that the two sports were similar. We can send the jury out on that one to decide whether it was done on purpose or not, but with three qualified barristers and a solicitor preparing the report, they have an extremely good way with words and it would be a difficult one to prove. So let’s keep digging by asking a similar question:

WHY DO WE THINK THAT THE ORIGIN OF RUGBY UNION LIES WITH THE WEBB ELLIS EVENT?

Firstly let’s look at the general outline of the report and its conclusions. The report is called ‘The Origin of Rugby Football’, which basically tells us that we are going to learn about the origin of rugby football if we read the report. From the second paragraph onwards it’s telling us that Matthew Holbeche Bloxam identifies the origin of the sport as being the William Webb Ellis Event, and we must therefore believe that this is indeed the origin of the sport:

“…and also to enquire into the account of the origin of our game put forward on more than one occasion by the late Mr. Matthew Holbeche Bloxam…” –

ORSR003

“We now come to Mr. Bloxam’s account of the origin of the present Rugby game…” –

ORSR009

“…that this was in all probability done in the latter half of 1823 by Mr. W. Webb Ellis, who is credited by Mr. Bloxam with the invention and whose ‘unfair practices’ were (according to Mr. Harris) the subject of general remark at the time.” –

ORSR022

The editor of the report is sure that Matthew Bloxam has pinpointed the origin of Rugby Union, but what did Matthew Bloxam actually say? The report includes Bloxam’s 1880 Meteor article which was written in response to a letter to The Times and which mentions his 1876 letter to the Standard Newspaper, as well as his later article of the same year in the Meteor. Perhaps these last two accounts should have been included in the report, along with another mention of Ellis in 1883. We should take a look at them just to see what Bloxam says. But first it’s worth noting that we are not alone in thinking that the report is a bit short of information. In WHD Rouse’s book ‘A History of Rugby School’, published in 1898 just one year after publication of the report, he says of it:

“Several sources of information have not been used for this book, which would have greatly increased its value. Chief of these is the Books of the Big Side Levée.” –

WRRS262

Indeed others have pointed to the lack of readily available information, so let’s go all the way back to the London Evening Standard letter of 1876. The Standard discussion is a chain of letters that originated from a small report about a football accident in which a young man named Ison died. Bloxam’s letter is the last in the chain and this is what he says:

“Sir, - Permit an old Rugbeian, at school under the headmastership of Dr. Wooll, who resigned that office in the summer of 1828, to say a few words on the point in controversy in the present Rugby game. The running with the ball in one’s hands is of no great antiquity as regards Rugby, it has there originated within the last half – century. It was not so during Dr. Wooll’s mastership. When a boy had caught the ball in his hands he was not allowed to run forwards with it, but marking with the heel of his foot the spot where he had caught it, he was permitted without molestation to go back on his own side as far as he chose, the opposite side not being allowed to cross the point where the ball had been caught. He who had caught the ball might then either punt it, or place it on the ground and kick it, or allow some one else on his side to kick it so placed; but directly the ball touched the ground, the opposite side might rush forward and contend.

Such was the rule of the game at Rugby School fifty years ago. MATTHEW HOLBECHE BLOXAM, at Rugby School from 1813 to 1821, and ever since a resident at Rugby.

Feb, 24.” – LEVS18760226

In this letter Matthew Bloxam says nothing about Webb Ellis. It was 53 years after William Webb Ellis had supposedly invented a game that nobody yet knew he had invented.

Bloxam wrote the above letter in February 1876 and following that he wrote three major articles on Football at Rugby School (October 1876, December 1880 & November 1883). This is what he says in Meteor No 104 published on 10 October 1876.

“FOOTBALL AND ATHLETICS

In the early part of the present year, some letters, written by old Rugbeians, about the present Rugby Football Game, appeared in the Standard, a well known London daily paper. In one of these letters the writer professed his belief that the Rugby School Football Game, at present played at Rugby, was of great and unknown antiquity. On this I wrote a letter, published in the Standard, to the effect that the present game, so far as the rules authorised the ball being taken up and carried by hand, the holder running with it, was unknown during the time I was at School, 1813 to 1821, and was I thought, introduced in Dr. Arnold’s time. I have since ascertained that this change originated with a Town boy or Foundationer of the name of Ellis, William Webb Ellis, who was entered at Rugby School in 1817, and left at Midsummer 1825, being then elected as second exhibitioner of that year. It must, I think, have been in the second half year of 1824, that this change from the former system, in which the football was not allowed to be taken up and run with, commenced. At first the new practice did not succeed, but was soon set aside, and not again introduced, by whom I know not, till Dr. Arnold’s mastership, 1828-42.

The game of Football was practised in this country before the middle of the 14th century. In 1349 it was, with other games, prohibited by authority, as interfering or supposing to interfere, with the practice of, and impending the progress of Archery.

In the early part of the 17th century it was discountenanced by James the First, who in his ‘Basilicon Doron’ says “From this Court I debarre all rough and violent exercises, as the football, meeter for lameing , than making able the users thereof.”

It is, I think, owing the condemnation of the game by this Monarch, that we do not find it mentioned in the “Annalia Dubrentia,” a collection of poetical effusions “upon the yearly celebration of Mr. Robert Dover’s Olimpick Games upon “Cotswold Hills.” These games, if not the origin, were the precursors of our present athletic sports. James the First gave them his sanction, and it may, I think, have been in compliment to him, that the game of football was omitted.

It continued, however, a game amongst countrymen in the 17th century, as appears from notice in the poems of Waller, born A.D 1605, died A.D. 1687:-

“As when a sort of lusty shepherds try

“Their force at Football; care of victory

“Makes them salute so rudely breast to breast

“That their encounter seems too rough for jest.”

But an earlier poet, Barclay, in his “Ship of Fools,” published A.D. 1508, treats of a game more resembling the present Rugby Football Game:-

“And now in the winter, when men kill the fat swine,

“They get the bladder and blow it great and thin,

“With many beans and peason put within:

“It ratleth, soundeth, and shineth clere and fayre,

“While it is throwen and cast up in the ayre,

“Eche one contendeth and hath a great delite

“With foote and with hands the bladder for to smite;

“If it fall to grounde, they lifte up agayne

“And this way to labour they count it nopayne,”

In conclusion, I may remark that the Rugby school footballs are well known all over the world…” – METR18761010

So in Bloxam’s letter to the Standard earlier that year there is no mention of Ellis, but in the above article in the Meteor eight months later, he mentions Ellis for the first time. It is also of interest that in this first mention of Ellis the date given for the event is 1824, but in the book ‘Rugby – The School and Neighbourhood’, this has been changed to 1823 by the editor Rev W. W. Payne Smith, M.A.:

“…so far as the rules authorised the ball being taken up and carried by hand, the holder running with it, was unknown during the time I was at School, 1813 to 1821, and was I thought, introduced in Dr. Arnold’s time. I have since ascertained that this change originated with a Town boy or Foundationer of the name of Ellis, William Webb Ellis…It must, I think, have been in the second half year of 1823, that this change from the former system, in which the football was not allowed to be taken up and run with, commenced. At first the new practice did not succeed, but was soon set aside, and not again introduced, by whom I know not, till Dr. Arnold’s mastership,

1828-42.” – MBRN110

In his article Bloxam states that there were rules when he played football 1813–1821 and that one of the rules has since changed. Then he gives us conflicting opinions. In one sentence he says that he thinks that this is when running with the ball started, and in the next sentence he says that it started but didn’t succeed, and was then started again by an unknown person 5–19 years later. He then adds information about folk football but doesn’t provide a link from folk football to Rugby School, only a similarity between the ball described in a 1508 poem and the Rugby School balls that are known worldwide. At no point does he say that Webb Ellis invented football or rugby; he just thinks that Webb Ellis started the change in one of the rules.

Back to the Old Rugbeian report. The one account that it relies on to attempt to prove that the Webb Ellis Event is the origin of Rugby Union is Matthew Bloxam’s Meteor article dated 1880. This is what Bloxam says in that article:

“In the latter half of 1823, some 57 years ago, originated, though without premeditation, that change in one of the rules which more than any other has since distinguished the Rugby School game from the Association

Rules.” – ORSR009

/ METR18801222

The important words in this paragraph are ‘originated’ and ‘change in one of the rules’, meaning that there is more than one rule, and that this is where the change in only one of those rules began. He does not say that this is the beginning of a new game. He does not say that Webb Ellis invented a game. He is saying that the game being played before and after the Webb Ellis event is the same game, but that one of the rules started to change. Ellis is playing an organized game with rules – Football at Rugby

School (Rugby Football). If he runs forward with ball, he is still playing Football at Rugby School, and the game remained as such until at least 1845 when the first rules were printed. Then, slowly as the game evolved and spread, it became football as played under Rugby School

Rules or Rugby Football.

Let’s look at the front cover and the title page of the first set of rules.

Please note again on the front cover Football Rules 1845, the title page heading FOOTBALL RULES and The following Rules…… as the LAWS OF FOOTBALL. This is the same football that Mathew Holbeche Bloxam was playing in 1813, only the rules have evolved

between 1813 and 1845 to include the action of running forward with the ball.

The final mention of Webb Ellis by Bloxam is in a paper that he read to the Natural History Society at Rugby School on 17 November 1883. The paper is published in the School Natural History Society Report for 1883:

"As to football, a different game was played to that at present; the rules were few and unwritten, but well understood. Two of the best players chose in a certain number on each side; the fags, all of whom were required to be present, unless specially excused by a Præpostor, were then divided in a rough and ready way, one half being sent to keep one goal, the other half the other goal. Any of the fags, who kept or were supposed to keep goal, might, however, follow up on that side by which their goal was defended, and this some of the juniors did, but at a respectful distance from the main body of the combatants, and as taking up the ball and running with it was not allowed, a kick at the ball was often obtained by a junior. The game was not then a scientific game; there were no matches to record, or press to record them. The taking up the ball first commenced in, I think, the year 1825, by a foundationer or town boy named Ellis; he was also a Praepostor. Had he not been of that grade in the school, he would, I think, have received more kicks than halfpence for breaking the rule. Backs and half-backs were unknown, each combatant, subject to a few fixed rules, played as he individually might list. Whilst keeping goal and immediate attention was not required, games were often played by juniors, an old glove, stuffed with leaves, serving as a substitute for a football. There was no change of apparel for football, no caps, no flannels; hat and coat, or jacket, were simply doffed. There were no matches between house and house, or between the school and foreign teams. All were scratch games and unreported, yet the games were played with as much zest as at present, though when finished the game was no longer thought of." –

MBRN074 / NHSR006

In his mention of Ellis, this time he’s changed the date to 1825 and he still doesn’t say that Webb Ellis invented a game. Bloxam seems to be unsure, his facts are all over the place, and I believe that he is beginning to doubt his source for the Webb Ellis story.

Summarising Bloxam’s three major articles that include the Webb Ellis event, he first says that it took place in 1824, then 1823, and finally 1825. He is unsure as to whether it ever happened, but even if it did he states that Webb Ellis only started the change in one of the rules. There is no sentence in which Bloxam states that Webb Ellis invented the game of Rugby Football or that this is where the origin of Rugby Football or Rugby Union lies. He does say that this is where the change in one of the rules originated, and this is his only reference to the word ‘origin’. As far as Bloxam is concerned, Webb Ellis was playing the same football that he played, which was also the same football that was played under Thomas Arnold 1828–1842 when the rules that allowed running forward with the ball commenced.

The Old Rugbeian report states:

“…the account of the origin of our game put forward on more than one occasion by the late Matthew Holbeche Bloxam…” –

ORSR003

“We now come to Mr Bloxam’s account of the origin of the present Rugby game…” –

ORSR009

“…that this is in all probability done in the latter half of 1823 by Mr W Webb Ellis, who is credited by Mr Bloxam with the invention and whose unfair practices were (according to Mr Harris) the subject of general remark at the time.” –

ORSR022

Did you see anywhere in Matthew Bloxam’s writings where he said that Webb Ellis had invented the game? I certainly didn’t. There’s a term for these types of statements – ‘misinformation’ – ‘false or inaccurate information, especially that which is deliberately intended to deceive’, as defined by the Oxford online dictionary. And deceive it still does, with the governing body of Rugby Union, World Rugby, still promoting the Webb Ellis event as being the origin of the sport.

|

Misinformation courtesy of

Wikipedia |

This illustration (from Wikipedia’s Rugby School page) continues to perpetuate the misinformation. Note the Association football goals in the background. It is impossible for these to have been at Rugby School in 1823 because that game was not created until

1863 and even then the first Association football goals did not have a crossbar.

(a goal could be

scored at any height).

SUMMARY – It is impossible for William Webb Ellis to have invented a game that he was already playing. The game that he was playing when he broke one of the rules was

'Football' at Rugby School (Rugby Football). Matthew Bloxam did not say that Webb Ellis invented the game; he said that he merely started the change in one of the rules. If Webb Ellis did catch the ball and run forward with it for the first time then he contributed to the evolution of the sport – the changing of actions, aims and rules. He did not invent Rugby Union. The report of the sub-committee of the Old Rugbeian Society has been proven to be biased towards naming the Webb Ellis Event as the origin. The report had no other purpose than to name Rugby School as the origin of the sport of Rugby Union. It is an extremely unsafe publication and the facts contained therein cannot be considered authentic unless they can be backed up by other independent sources.

CONCLUSION – It is impossible for

the origin of Rugby Football or Rugby Union Football to be the William Webb Ellis

Event in 1823, 1824 or 1825.

|